1906 San Francisco earthquake

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaAt 5:12 a.m. on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (Extreme). High-intensity shaking was felt from Eureka on the North Coast to the Salinas Valley, an agricultural region to the south of the San Francisco Bay Area. Devastating fires soon broke out in San Francisco and lasted for several days. More than 3,000 people died, and over 80 percent of the city was destroyed. The events are remembered as one of the worst and deadliest earthquakes in the history of the United States. The death toll remains the greatest loss of life from a natural disaster in California's history and high on the lists of American disasters.

Earthquake

USGS ShakeMap showing the earthquake's intensity

The 1906 earthquake preceded the development of the Richter magnitude scale by three decades. The most widely accepted estimate for the magnitude of the quake on the modern moment magnitude scale is 7.9; values from 7.7 to as high as 8.3 have been proposed.[8] According to findings published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, severe deformations in the earth's crust took place both before and after the earthquake's impact. Accumulated strain on the faults in the system was relieved during the earthquake, which is the supposed cause of the damage along the 450-kilometre-long (280 mi) segment of the San Andreas plate boundary.[8] The 1906 rupture propagated both northward and southward for a total of 296 miles (476 km).[9] Shaking was felt from Oregon to Los Angeles, and as far inland as central Nevada.

A strong foreshock preceded the main shock by about 20 to 25 seconds. The strong shaking of the main shock lasted about 42 seconds. There were decades of minor earthquakes – more than at any other time in the historical record for northern California – before the 1906 quake. Previously interpreted as precursory activity to the 1906 earthquake, they have been found to have a strong seasonal pattern and are now believed to be due to large seasonal sediment loads in coastal bays that overlie faults as a result of the erosion caused by hydraulic mining in the later years of the California Gold Rush.

For years, the epicenter of the quake was assumed to be near the town of Olema, in the Point Reyes area of Marin County, due to local earth displacement measurements. In the 1960s, a seismologist at UC Berkeley proposed that the epicenter was more likely offshore of San Francisco, to the northwest of the Golden Gate. The most recent analyses support an offshore location for the epicenter, although significant uncertainty remains.[2] An offshore epicenter is supported by the occurrence of a local tsunami recorded by a tide gauge at the San Francisco Presidio; the wave had an amplitude of approximately 3 inches (7.6 cm) and an approximate period of 40–45 minutes.

Analysis of triangulation data before and after the earthquake strongly suggests that the rupture along the San Andreas Fault was about 500 kilometres (310 mi) in length, in agreement with observed intensity data. The available seismological data support a significantly shorter rupture length, but these observations can be reconciled by allowing propagation at speeds above the S-wave velocity (supershear). Supershear propagation has now been recognized for many earthquakes associated with strike-slip faulting.

Recently, using old photographs and eyewitness accounts, researchers were able to estimate the location of the hypocenter of the earthquake as offshore from San Francisco or near the city of San Juan Bautista, confirming previous estimates.

Damage

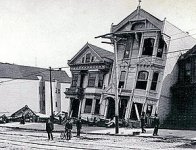

Damaged houses on Howard Street

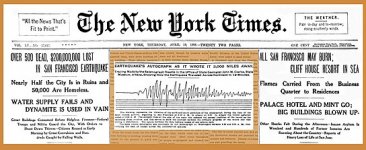

Seismographs on the U.S. east coast recorded the earthquake some 19 minutes later; some early death estimates exceeded 500.

Early death counts ranged from 375 to over 500. However, hundreds of fatalities in Chinatown went ignored and unrecorded. The total number of deaths is still uncertain, but various reports presented a range of 700–3,000+. In 2005, the city's Board of Supervisors voted unanimously in support of a resolution written by novelist James Dalessandro ("1906") and city historian Gladys Hansen ("Denial of Disaster") to recognize the figure of 3,000 plus as the official total. Most of the deaths occurred in San Francisco itself, but 189 were reported elsewhere in the Bay Area; nearby cities, such as Santa Rosa and San Jose, also suffered severe damage. In Monterey County, the earthquake permanently shifted the course of the Salinas River near its mouth. Where previously the river emptied into Monterey Bay between Moss Landing and Watsonville, it was diverted 6 miles (9.7 km) south to a new channel just north of Marina.

Between 227,000 and 300,000 people were left homeless out of a population of about 410,000; half of those who evacuated fled across the bay to Oakland and Berkeley. Newspapers described Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, the Panhandle and the beaches between Ingleside and North Beach as covered with makeshift tents. More than two years later, many of these refugee camps were still in operation.

The earthquake and fire left long-standing and significant pressures on the development of California. At the time of the disaster, San Francisco had been the ninth-largest city in the United States and the largest on the West Coast, with a population of about 410,000. Over a period of 60 years, the city had become the financial, trade, and cultural center of the West; operated the busiest port on the West Coast; and was the "gateway to the Pacific", through which growing U.S. economic and military power was projected into the Pacific and Asia. Over 80% of the city was destroyed by the earthquake and fire. Though San Francisco rebuilt quickly, the disaster diverted trade, industry, and population growth south to Los Angeles, which during the 20th century became the largest and most important urban area in the West. Many of the city's leading poets and writers retreated to Carmel-by-the-Sea where, as "The Barness", they established the arts colony reputation that continues today.

The 1908 Lawson Report, a study of the 1906 quake led and edited by Professor Andrew Lawson of the University of California, showed that the same San Andreas Fault which had caused the disaster in San Francisco ran close to Los Angeles as well. The earthquake was the first natural disaster of its magnitude to be documented by photography and motion picture footage and occurred at a time when the science of seismology was blossoming.

Fires

Arnold Genthe's photograph, looking toward the fire on Sacramento Street

As damaging as the earthquake and its aftershocks were, the fires that burned out of control afterward were even more destructive. It has been estimated that up to 90% of the total destruction was the result of the subsequent fires. Within three days, over 30 fires, caused by ruptured gas mains, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings on 490 city blocks. Some were started when San Francisco Fire Department firefighters, untrained in the use of dynamite, attempted to demolish buildings to create firebreaks. The dynamited buildings themselves often caught fire. The city's fire chief, Dennis T. Sullivan, who would have been responsible for coordinating firefighting efforts, had died from injuries sustained in the initial quake. In total, the fires burned for four days and nights.

Due to a widespread practice by insurers to indemnify San Francisco properties from fire, but not earthquake damage, most of the destruction in the city was blamed on the fires. Some property owners deliberately set fire to damaged properties, to claim them on their insurance. Capt. Leonard D. Wildman of the U.S. Army Signal Corps reported that he "was stopped by a fireman who told me that people in that neighborhood were firing their houses...they were told that they would not get their insurance on buildings damaged by the earthquake unless they were damaged by fire".

Burning of the Mission District (left) and a map showing the extent of the fire

One landmark building lost in the fire was the Palace Hotel, subsequently rebuilt, which had many famous visitors, including royalty and celebrated performers. It was constructed in 1875 primarily financed by Bank of California co-founder William Ralston, the "man who built San Francisco". In April 1906, the tenor Enrico Caruso and members of the Metropolitan Opera Company came to San Francisco to give a series of performances at the Grand Opera House. The night after Caruso's performance in Carmen, the tenor was awakened in the early morning in his Palace Hotel suite by a strong jolt. Clutching an autographed photo of President Theodore Roosevelt, Caruso made an effort to get out of the city, first by boat and then by train, and vowed never to return to San Francisco. Caruso died in 1921, having remained true to his word. The Metropolitan Opera Company lost all of its traveling sets and costumes in the earthquake and ensuing fires.

Some of the greatest losses from fire were in scientific laboratories. Alice Eastwood, the curator of botany at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, is credited with saving nearly 1,500 specimens, including the entire type specimen collection for a newly discovered and extremely rare species, before the remainder of the largest botanical collection in the western United States was destroyed in the fire. The entire laboratory and all the records of Benjamin R. Jacobs, a biochemist who was researching the nutrition of everyday foods, were destroyed. The original California flag used in the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt at Sonoma, which at the time was being stored in a state building in San Francisco, was also destroyed in the fire.

The fire following the earthquake in San Francisco cost an estimated $350 million at the time (equivalent to $7.75 billion in 2020). The devastating quake leveled about 80% of the city.