Chicago Fire Department Line of Duty Deaths

https://www.facebook.com/fireservicelineofdutydeaths/#DECEMBER 22, 1910 - CHICAGO, IL 21 Firefighters Killed.

On December 22, 1910, The Chicago Union Stock Yards Fire resulted in the deaths of 21 firefighters, which until September 11, 2001 was the largest single instance of firefighter line of duty deaths in the United States.

It was 24 degrees outside at 4 a.m. on Dec. 22, 1910, the first full day of winter. In the unlit basement of a packing house in the Union Stock Yards, that coal-black cold was being replaced by the glow of sparking wires, and then the first flames of a fire fed by combustibles ranging from rags to raw meat.

Within little more than an hour, that fire would grow to engulf warehouse No. 7 of the Morris & Co. plant. Then, in a few horrendous seconds, it would turn the nearly windowless brick building at 44th and Loomis streets from just another meat-packing operation into a graveyard.

Until the collapse of the World Trade Center’s twin towers on Sept. 11, 2001, no single disaster in the history of the United States claimed the lives of more firefighters.

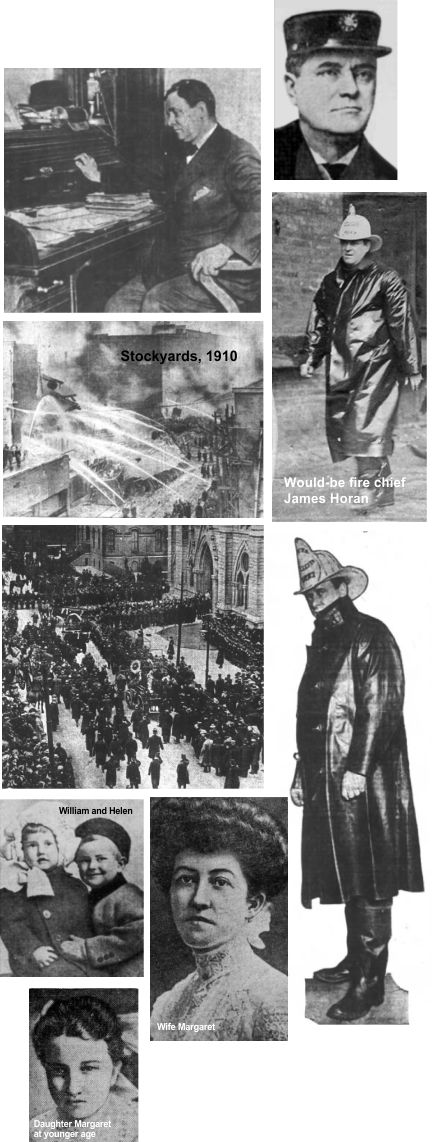

When the fire broke out, all of the firefighters in the stockyards rushed to the scene in their horse-drawn steam engines and trucks, and Fire Marshal James Horan woke up in the wee hours to drive the only motorized department vehicle, the Chicago Tribune recalled.

The 51-year-old fire chief arrived on the scene less than an hour after the first alarm, and only 18 minutes after the 4-11 alarm bell rang at his house and roused him from a short night’s sleep.

Firefighters encountered difficulty from the start, according to Bill Cattorini, a lieutenant with Chicago Fire Department Engine 49 and an expert on the history of the fire. “It was very difficult to fight a fire in there because there were no windows. It was eight stories high, and so they knew there was going to be a battle, but it just so happened that a wall came down unexpectedly, and buried them,” he said.

A nearby loading dock was the only place from where the fire could be attacked, and access was restricted by a rail line filled with box cars running down the center of Loomis Street.

At 5:08 a.m., 59 minutes after the first alarm, a six-story brick wall, buckled by the expanding superheated air in the building, crashed through a wooden canopy onto a loading dock, killing Horan and his colleagues. The tons of flaming debris buried them alive. Hours later, after firemen removed the debris brick by brick, Horan’s body was found. He was on his knees, arms folded, facing the center of the fire.

Those who survived were either blown sideways by the force of the collapse, which destroyed the box cars, or in some instances, were lucky enough to have enough distance to dash away. But most had nowhere to go, even after Horan warned them to “look out.” A century later to the day, two firefighters are dead and 16 are injured, after a wall and roof collapsed as they fought a fire at 1744 E. 75th St.

Initial Hazards & Delays

Two major hazards contributed to the fire’s strength and rate of spread: the animal fat and grease that coated the walls of the warehouse, and the hundreds of cured hogs inside, which were preserved with saltpeter, one of the main ingredients in gunpowder.

Upon arrival at the warehouse, Chicago-area firefighters found themselves completely helpless against the growing inferno, as all the nearby fire hydrants had been shut off to prevent freezing. By the time firefighters were able to activate the valves that fed the hydrants, it was too late. The warehouse was completely involved.

To make matters worse, the building was surrounded by various railway cars, brick walls and other warehouses, which prevented firefighters from accessing the warehouse’s upper floor windows. Had they been able to reach the windows, they could have opened them to release the air pressure that was building up inside the structure.

The Blast

At about 0500 HRS, the pressure inside the warehouse could no longer be contained. One firefighter on scene said he saw the walls bulge and immediately shouted a warning to others on scene. The building exploded, causing the entire structure to crumble. A 6' wall of the building collapsed onto the nearby loading dock, killing the 21 firefighters.

The blast also caused a second fire to start in a nearby seven-story warehouse, making the scene even more chaotic. But many firefighters paid little attention to the second fire. Instead, they made a desperate attempt to uncover the 21 men who had been buried in the rubble. They frantically dug with their hands, throwing bricks off the scorching-hot pile in a futile attempt to rescue those who had obviously perished. They had to be ordered to stop digging and continue with the firefight.

With what little command structure was left, several additional alarms were called, which resulted in more than 50 engine companies and hundreds of off-duty firefighters responding to the scene.

Upon hearing of the fire, relatives and friends of the deceased flocked to the scene. Both firefighters and civilians took part in uncovering the bodies, but water had to first be poured onto the pile to make it cool enough for the digging to resume. It took 24 hours for firefighters to knock down the fire and recover all 21 bodies.

According to reports, an ammonia pipe caused the explosion. The fire started by a faulty electrical socket, left behind 19 widows and 35 orphaned children just before Christmas Day. The fire chief's body was found 14-1/2 hours after the collapse. The last body recovered was that of Captain Doyle, of Engine 39. His son, Firefighter Nicholas Doyle, of Truck 11, was also killed in the collapse. The entire company of Truck 11 was killed in the collapse. The First Assistant Chief went on to become the fire chief and was the fire commissioner when the 1934 conflagration destroyed a good part of the sprawling stockyards. So that he could be home with his family on Christmas Day, Lieutenant Brandenberg, of Truck 11, traded his days off with another man. Lieutenant Fitzgerald, of Engine 23, was to be married Christmas Eve. Firefighter Schonsett, of Truck 11, died on his birthday and his third wedding anniversary was on Christmas Eve. Firefighter Weber, of Engine 59, had just moved his family into their new home a few days earlier. The chief of Battalion 11, who was the first chief at the scene of this fire, was killed in a collision on November 8, 1916, as he responded to another fire in the stockyards.

CHIEF FIRE MARSHALL JAMES J. HORAN, 51

2ND ASST. FIRE MARSHALL WILLIAM J. BURROUGHS, 47 HEADQUARTERS

CAPTAIN PATRICK E. COLLINS, 47 ENGINE CO. 59

CAPTAIN DENNIS DOYLE, 46 ENGINE CO. 39

CAPTAIN ALEXANDER LANNON, 40 ENGINE CO 50

LIEUTENANT WILLIAM G. STURM, 46 ENGINE CO. 64

LIEUTENANT HERMAN G. BRANDENBERG, 41 TRUCK CO. 11

LIEUTENANT JAMES J. FITZGERALD, 33 ENGINE CO. 23

LIEUTENANT EDWARD J. DANIS, 46 ENGINE CO. 61

TRUCKMAN NICHOLAS D. DOYLE, 25 TRUCK CO. 11

TRUCKMAN EDWARD D. SCHONSETT, 27 TRUCK CO. 11

TRUCKMAN ALBERT J. MORIARTY, 34 TRUCK CO. 11

TRUCKMAN MICHAEL F. McINERNEY, 32 TRUCK CO. 11

TRUCKMAN PETER J. POWERS, 34 TRUCK CO. 11

TRUCKMAN CHARLES N. MOORE, 29 TRUCK CO. 18

TRUCKMAN NICHOLAS CRANE, 34 TRUCK CO. 18

PIPEMAN THOMAS J. COSTELLO, 34 ENGINE CO. 29

PIPEMAN FRANK W. WALTERS, 46 ENGINE CO. 59

PIPEMAN GEORGE F. MURAWSKI, 37 ENGINE CO. 49

PIPEMAN GEORGE E. ENTHOF, 31 ENGINE CO. 23

DRIVER WILLIAM F. WEBER, 34 ENGINE CO. 59