December 30, 1903 - Fire at Chicago’s Iroquois Theater Kills 602 People.

A terrible blaze occurred at the Iroquois Theater on December 30, 1903 as a fire broke out in the crowded theater during a performance of a vaudeville show, starring the popular comedian Eddie Foy. The fire was believed to have been started by faulty wiring leading to a spotlight and claimed the lives of hundreds of people, including children, who were packed into the afternoon show for the holidays. The Iroquois Theater, the newest and most beautiful showplace in Chicago in 1903, was believed to be "absolutely fireproof". The Chicago Tribune called it a "virtual temple of beauty" but just five weeks after it opened its doors, it became a blazing death trap. The new theater was much acclaimed, even before it opened. It was patterned after the Opera Cominque in Paris and was located downtown on the north side of Randolph Street, between State and Dearborn. The interior of the four-story building was magnificent, with stained glass and polished wood throughout.

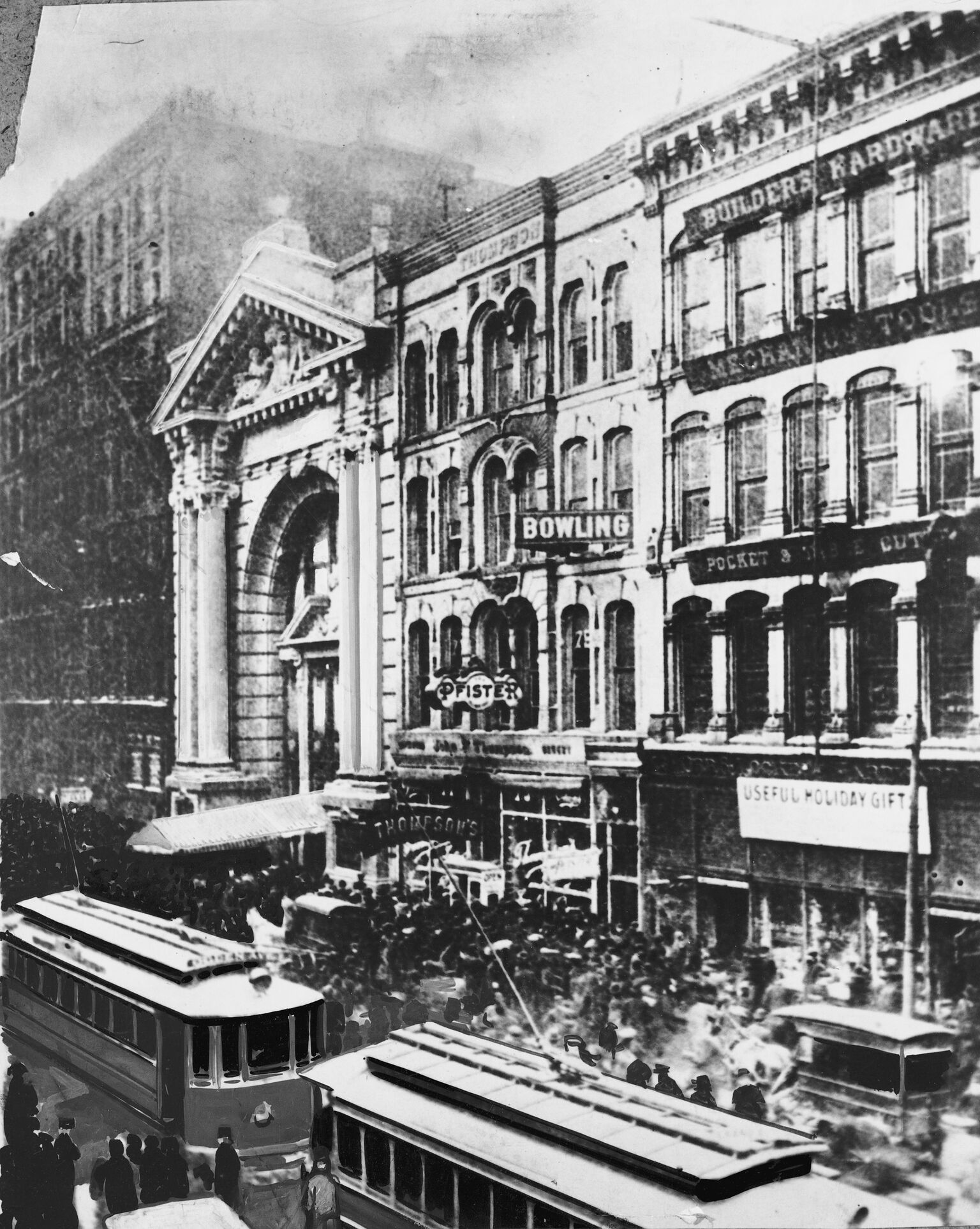

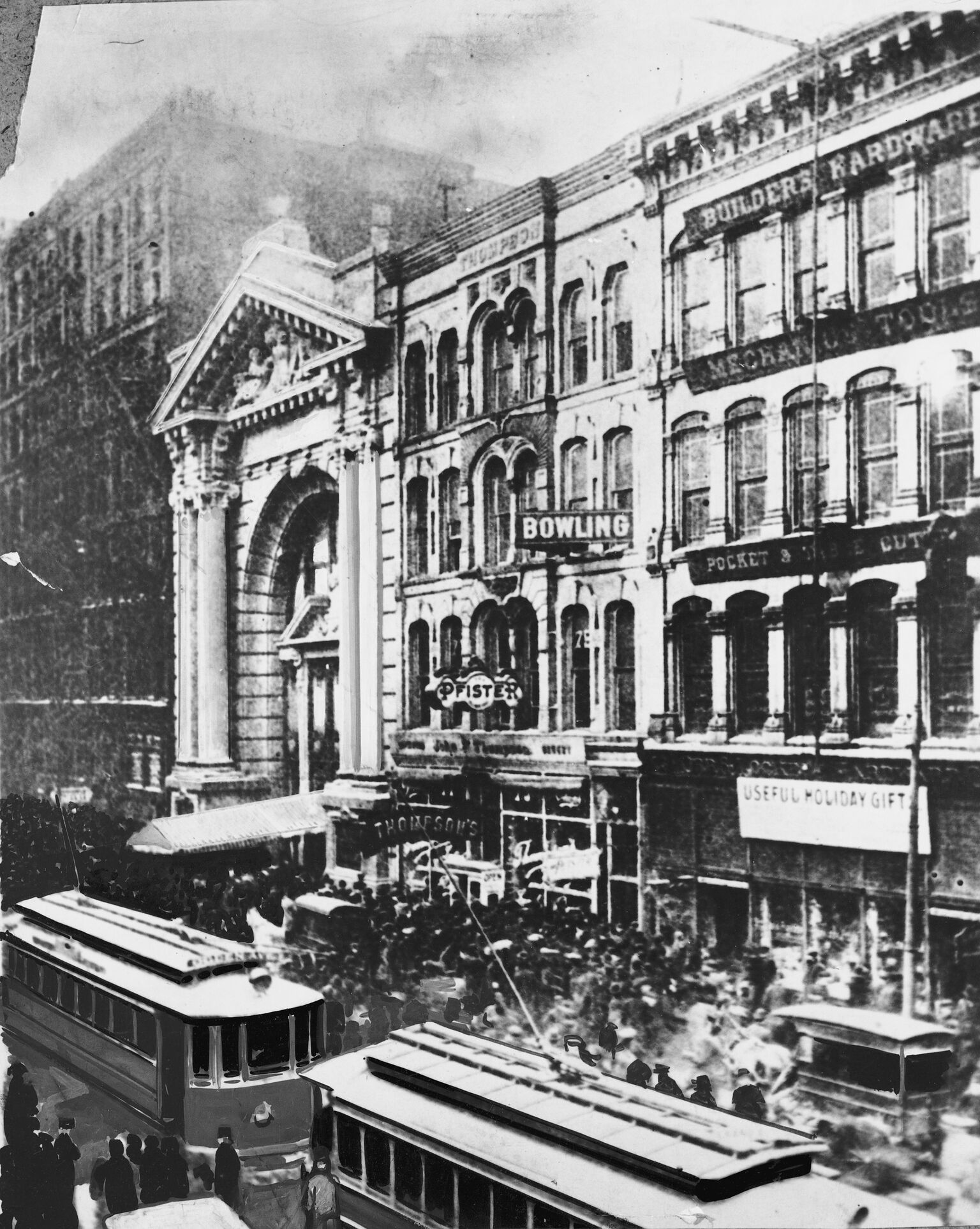

The lobby had an ornate 60-foot-high ceiling and featured white marble walls fitted with large mirrors that were framed in gold leaf and stone. Two grand staircases led away from either side of the lobby to the balcony areas as well. Outside, the building’s front façade resembled a Greek temple with a towering stone archway that was supported by massive columns. Thanks to the dozens of fires that had occurred over the years in theaters, architect Benjamin H. Marshall wanted to assure the public that the Iroquois was safe. He studied a number of fires that had occurred in the past and made every effort to make sure that no tragedy would occur in the new theater. The Iroquois had 25 exits that, it was claimed, could empty the building in less than five minutes. The stage had also been fitted with an asbestos curtain that could be quickly lowered to protect the audience. And while all of this was impressive, it was not enough to battle the real problems that existed with the Iroquois. Seats in the theater were wooden and stuffed with hemp and much of the precautionary fire equipment that was advertised to have been installed, never actually made it into the building. The theater had no fire alarms and in a rush to open the theater on time, other safety factors had been forgotten or simply ignored. The horrific events began on a bitterly cold December 30 of 1903. A holiday crowd had packed into the theater on that Wednesday afternoon to see a matinee performance of the hit comedy Mr. Blubeard. Officially, the Iroquois seated 1,600 people but with school out for Christmas break, it is believed there was an overflow crowd of nearly 2,000 people filling the seats and standing four-deep in the aisles. Another crowd filled the backstage area with 400 actors, dancers and stagehands hidden from those in the auditorium. Around 3:20 p.m., at the beginning of the second act, stagehands noticed a spark descend from an overhead light, and then some scraps of burning paper that fell down onto the stage. In moments, flames began licking at the red-velvet curtain and while a collective gasp went up from the audience, no one rushed for the exits. It has been surmised that the audience merely thought the fire was part of the show.

Although in his dressing room, applying his final makeup for the act, Eddie Foy heard the commotion outside and rushed out onto the stage to see what was going on. He implored the audience to remain seated and calm, assuring them that the theater was fireproof and that everyone was safe. He signaled conductor Herbert Gillea to play and the music had a temporary soothing effect on the crowd, which was growing restless. A few moments later, a flaming set crashed down onto the stage and Foy signaled a stagehand to lower the asbestos curtain to protect the audience. Unfortunately though, the curtain snagged halfway down, leaving a 20-foot gap between the bottom of the curtain and the wooden stage. The other actors in the show remained composed until they too realized what was happening. Many of them panicked and several chorus girls fainted and had to be dragged off-stage. The audience began to scream and panic too and a mad rush was started for the Randolph Street exit from the theater. Foy made one last attempt to calm the audience and then he fled to a rear exit. With children in tow, the audience members immediately clogged the gallery and the upper balconies. The aisles had become impassable and as the lights went out, the crowd milled about in blind terror. The auditorium began to fill with heat and smoke and screams echoed off the walls and ceilings.

Through it all, the mass continued to move forward but when the crowd reached the doors, they could not open them as they had been designed to swing inward rather than outward. The crush of people prevented those in the front from opening the doors. To make matters worse, some of the side doors to the auditorium were reportedly locked. Many of those who died not only burned, but suffocated from the smoke and the crush of bodies as well. Later, as the police removed the charred remains from the theater, they discovered that a number of victims had been trampled in the panic. One dead woman’s face even bore the mark of a shoe heel. Backstage, theater employees and cast members opened a rear set of double doors, which sucked the wind inside and caused flames to fan out under the asbestos curtain and into the auditorium. A second gust of wind created a fireball that shot out into the galleries and balconies that were filled with people. All of the stage drops were now on fire and as they burned, they engulfed the supposedly noncombustible asbestos curtain and when it collapsed, it plunged into the seats of the theater.

The scene outside of the theater was completely normal and most accounts say that the fire was burning for almost 15 minutes before any smoke was noticed by those passing by. Because there was no fire alarm box outside, someone ran around the corner to sound the alarm at Engine Co. 13. Things were so quiet in front of the Iroquois though that the first firefighters to arrive thought it was a false alarm. This changed when they tried to open the auditorium doors and found they could not --- there were too many bodies stacked up against them. Another alarm was sounded as the firemen tried to get into the building. They were only able to gain access by actually pulling the bodies out of the way with pike poles, peeling them off one another and then climbing over the stacks of corpses. It took only ten minutes to put out the remaining blaze, as the intense heat inside had already eaten up anything that would still burn. The firefighters made their way into the blackened auditorium and were met with only silence and smell of death. They called out for survivors but no one answered their cry.

The gallery and upper balconies sustained the greatest loss of life as the patrons had been trapped by locked doors at the top of the stairways. The firefighters found 200 bodies stacked there, as many as 10 deep. Those who escaped had literally ripped the metal bars from the front of the balcony and had jumped onto the crowds below. Even then, most of these met their deaths at a lower level. A few who made it to the fire escape door behind the top balcony found that the iron staircase was missing. In its place was a platform that plunged about 100 feet to the cobblestone alley below. Across the alley, behind the theater, painters were working on a building occupied by Northwestern University’s dental school. When they realized what was happening at the theater, they quickly erected a makeshift bridge using ladders and wooden planks, which they extended across the alley to the fire escape platform. Reports vary as to how many they saved, but it’s thought that it may have been as many as 12, although it’s also believed that at least seven people fell to their deaths from the "bridge". Others say that many times that number jumped from the ledge or were pushed by the milling crowd that pressed through the doors behind them. The passageway behind the theater is still referred to as "Death Alley" today, after nearly 150 victims were found piled here -- stacked by the firemen or having fallen to their fates.

When it was all over, 572 people died in the fire and more died later, bringing the eventual death toll up to 602, including 212 children. For nearly five hours, police officers, firemen and even newspaper reporters, carried out the dead. Anxious relatives sifted through the remains, searching for loved ones. Other bodies were taken away by police wagons and ambulances and transported to a temporary morgue at Marshall Field’s on State Street. Medical examiners and investigators worked all through the night.

The next day, the newspapers devoted full pages to lists of the known dead and injured. News wires carried reports of the tragedy around the country and it soon became a national disaster. Chicago mayor Carter Harrison, Jr. issued an order that banned public celebration on New Year’s Eve, closing the night clubs and making forbidden any fireworks or sounding of horns. Every church and factory bell in the city was silenced and on January 2, 1904, the city observed an official day of mourning.

Someone, the public cried, had to answer for the fire and an investigation of the blaze brought to light a number of troubling facts. The investigation discovered that two vents of the building‘s roof, which had not been completed in time for the theater’s opening, were supposed to filter out smoke and poisonous gases in case of a fire. However, the unfinished vents had been nailed shut to keep out rain and snow. That meant that the smoke had nowhere to go but back into the theater, literally suffocating those audience members who were not already burned to death. Another finding showed that the supposedly "fireproof" asbestos curtain was really made from cotton and other combustible materials. It would have never saved anyone at all. In addition to not having any fire alarms in the building, the owners had decided that sprinklers were too unsightly and too costly and had never had them installed. To make matters worse, the management also established a policy to keep non-paying customers from slipping into the theater during a performance --- they quietly bolted nine pair of iron panels over the rear doors and installed padlocked, accordion-style gates at the top of the interior second and third floor stairway landings. And just as tragic was the idea they came up with to keep the audience from being distracted during a show. They ordered all of the exit lights to be turned off! One exit sign that was left on led only to ladies restroom and another to a locked door for a private stairway. And as mentioned already, the doors of the outside exits, which were supposed to make it possible for the theater to empty in five minutes, opened to the inside, not to the outside.

The investigation led to a cover-up by officials from the city and the fire department, who denied all knowledge of fire code violations. They blamed the inspectors, who had overlooked the problems in exchange for free theater passes. A grand jury indicted a number of individuals, including the theater owners, fire officials and even the mayor. No one was ever charged with a criminal act though. Families of the dead filed nearly 275 civil lawsuits against the theater but no money was ever collected. The Iroquois Theater Company filed for bankruptcy soon after the disaster. The Iroquois Theater Fire ranks as the nation’s fourth deadliest blaze and the deadliest single building fire in American history. Nevertheless, the building was repaired and re-opened briefly in 1904 as Hyde and Behmann’s Music Hall and then in 1905 as the Colonial Theater. In 1924, the building was razed to make room for a new theater, the Oriental, but the façade of the Iroquois was used in its construction. The Oriental operated at what is now 24 West Randolph Street until the middle part of 1981, when it fell into disrepair and was closed down. It opened again as the home to a wholesale electronics dealer for a time and then went dark again. The restored theater is now part of the Civic Tower Building and is next door to the restored Delaware Building. It reopened as the Ford Center for the Performing Arts in 1998.

But this has not stopped the tales of the old Iroquois Theater from being told, especially in light of more recent, and more ghostly events. According to recent accounts from people who live and work in this area, "Death Alley" is not as empty as it appears to be. The narrow passageway, which runs behind the Oriental Theater, is rarely used today, except for the occasional delivery truck or a lone pedestrian who is in a hurry to get somewhere else. It is largely deserted, but why? The stories say that those a few who do pass through the alley often find themselves very uncomfortable and unsettled here. They say that faint cries are sometimes heard in the shadows and that some have reported being touched by unseen hands and by eerie cold spots that seem to come from nowhere and vanish just as quickly.

Chicago Fire Dept.- Iroquois Theatre Fire

https://youtu.be/spzAGnNwaUg

The 1903 Iroquois Theater Fire - Chicago (HQ)

https://youtu.be/WARJ1YuJLTU

Iroquois Theatre Fire Documentary H 264 for Apple TV

https://youtu.be/LKOKWcnU8nA

www.smithsonianmag.com

www.smithsonianmag.com

A terrible blaze occurred at the Iroquois Theater on December 30, 1903 as a fire broke out in the crowded theater during a performance of a vaudeville show, starring the popular comedian Eddie Foy. The fire was believed to have been started by faulty wiring leading to a spotlight and claimed the lives of hundreds of people, including children, who were packed into the afternoon show for the holidays. The Iroquois Theater, the newest and most beautiful showplace in Chicago in 1903, was believed to be "absolutely fireproof". The Chicago Tribune called it a "virtual temple of beauty" but just five weeks after it opened its doors, it became a blazing death trap. The new theater was much acclaimed, even before it opened. It was patterned after the Opera Cominque in Paris and was located downtown on the north side of Randolph Street, between State and Dearborn. The interior of the four-story building was magnificent, with stained glass and polished wood throughout.

The lobby had an ornate 60-foot-high ceiling and featured white marble walls fitted with large mirrors that were framed in gold leaf and stone. Two grand staircases led away from either side of the lobby to the balcony areas as well. Outside, the building’s front façade resembled a Greek temple with a towering stone archway that was supported by massive columns. Thanks to the dozens of fires that had occurred over the years in theaters, architect Benjamin H. Marshall wanted to assure the public that the Iroquois was safe. He studied a number of fires that had occurred in the past and made every effort to make sure that no tragedy would occur in the new theater. The Iroquois had 25 exits that, it was claimed, could empty the building in less than five minutes. The stage had also been fitted with an asbestos curtain that could be quickly lowered to protect the audience. And while all of this was impressive, it was not enough to battle the real problems that existed with the Iroquois. Seats in the theater were wooden and stuffed with hemp and much of the precautionary fire equipment that was advertised to have been installed, never actually made it into the building. The theater had no fire alarms and in a rush to open the theater on time, other safety factors had been forgotten or simply ignored. The horrific events began on a bitterly cold December 30 of 1903. A holiday crowd had packed into the theater on that Wednesday afternoon to see a matinee performance of the hit comedy Mr. Blubeard. Officially, the Iroquois seated 1,600 people but with school out for Christmas break, it is believed there was an overflow crowd of nearly 2,000 people filling the seats and standing four-deep in the aisles. Another crowd filled the backstage area with 400 actors, dancers and stagehands hidden from those in the auditorium. Around 3:20 p.m., at the beginning of the second act, stagehands noticed a spark descend from an overhead light, and then some scraps of burning paper that fell down onto the stage. In moments, flames began licking at the red-velvet curtain and while a collective gasp went up from the audience, no one rushed for the exits. It has been surmised that the audience merely thought the fire was part of the show.

Although in his dressing room, applying his final makeup for the act, Eddie Foy heard the commotion outside and rushed out onto the stage to see what was going on. He implored the audience to remain seated and calm, assuring them that the theater was fireproof and that everyone was safe. He signaled conductor Herbert Gillea to play and the music had a temporary soothing effect on the crowd, which was growing restless. A few moments later, a flaming set crashed down onto the stage and Foy signaled a stagehand to lower the asbestos curtain to protect the audience. Unfortunately though, the curtain snagged halfway down, leaving a 20-foot gap between the bottom of the curtain and the wooden stage. The other actors in the show remained composed until they too realized what was happening. Many of them panicked and several chorus girls fainted and had to be dragged off-stage. The audience began to scream and panic too and a mad rush was started for the Randolph Street exit from the theater. Foy made one last attempt to calm the audience and then he fled to a rear exit. With children in tow, the audience members immediately clogged the gallery and the upper balconies. The aisles had become impassable and as the lights went out, the crowd milled about in blind terror. The auditorium began to fill with heat and smoke and screams echoed off the walls and ceilings.

Through it all, the mass continued to move forward but when the crowd reached the doors, they could not open them as they had been designed to swing inward rather than outward. The crush of people prevented those in the front from opening the doors. To make matters worse, some of the side doors to the auditorium were reportedly locked. Many of those who died not only burned, but suffocated from the smoke and the crush of bodies as well. Later, as the police removed the charred remains from the theater, they discovered that a number of victims had been trampled in the panic. One dead woman’s face even bore the mark of a shoe heel. Backstage, theater employees and cast members opened a rear set of double doors, which sucked the wind inside and caused flames to fan out under the asbestos curtain and into the auditorium. A second gust of wind created a fireball that shot out into the galleries and balconies that were filled with people. All of the stage drops were now on fire and as they burned, they engulfed the supposedly noncombustible asbestos curtain and when it collapsed, it plunged into the seats of the theater.

The scene outside of the theater was completely normal and most accounts say that the fire was burning for almost 15 minutes before any smoke was noticed by those passing by. Because there was no fire alarm box outside, someone ran around the corner to sound the alarm at Engine Co. 13. Things were so quiet in front of the Iroquois though that the first firefighters to arrive thought it was a false alarm. This changed when they tried to open the auditorium doors and found they could not --- there were too many bodies stacked up against them. Another alarm was sounded as the firemen tried to get into the building. They were only able to gain access by actually pulling the bodies out of the way with pike poles, peeling them off one another and then climbing over the stacks of corpses. It took only ten minutes to put out the remaining blaze, as the intense heat inside had already eaten up anything that would still burn. The firefighters made their way into the blackened auditorium and were met with only silence and smell of death. They called out for survivors but no one answered their cry.

The gallery and upper balconies sustained the greatest loss of life as the patrons had been trapped by locked doors at the top of the stairways. The firefighters found 200 bodies stacked there, as many as 10 deep. Those who escaped had literally ripped the metal bars from the front of the balcony and had jumped onto the crowds below. Even then, most of these met their deaths at a lower level. A few who made it to the fire escape door behind the top balcony found that the iron staircase was missing. In its place was a platform that plunged about 100 feet to the cobblestone alley below. Across the alley, behind the theater, painters were working on a building occupied by Northwestern University’s dental school. When they realized what was happening at the theater, they quickly erected a makeshift bridge using ladders and wooden planks, which they extended across the alley to the fire escape platform. Reports vary as to how many they saved, but it’s thought that it may have been as many as 12, although it’s also believed that at least seven people fell to their deaths from the "bridge". Others say that many times that number jumped from the ledge or were pushed by the milling crowd that pressed through the doors behind them. The passageway behind the theater is still referred to as "Death Alley" today, after nearly 150 victims were found piled here -- stacked by the firemen or having fallen to their fates.

When it was all over, 572 people died in the fire and more died later, bringing the eventual death toll up to 602, including 212 children. For nearly five hours, police officers, firemen and even newspaper reporters, carried out the dead. Anxious relatives sifted through the remains, searching for loved ones. Other bodies were taken away by police wagons and ambulances and transported to a temporary morgue at Marshall Field’s on State Street. Medical examiners and investigators worked all through the night.

The next day, the newspapers devoted full pages to lists of the known dead and injured. News wires carried reports of the tragedy around the country and it soon became a national disaster. Chicago mayor Carter Harrison, Jr. issued an order that banned public celebration on New Year’s Eve, closing the night clubs and making forbidden any fireworks or sounding of horns. Every church and factory bell in the city was silenced and on January 2, 1904, the city observed an official day of mourning.

Someone, the public cried, had to answer for the fire and an investigation of the blaze brought to light a number of troubling facts. The investigation discovered that two vents of the building‘s roof, which had not been completed in time for the theater’s opening, were supposed to filter out smoke and poisonous gases in case of a fire. However, the unfinished vents had been nailed shut to keep out rain and snow. That meant that the smoke had nowhere to go but back into the theater, literally suffocating those audience members who were not already burned to death. Another finding showed that the supposedly "fireproof" asbestos curtain was really made from cotton and other combustible materials. It would have never saved anyone at all. In addition to not having any fire alarms in the building, the owners had decided that sprinklers were too unsightly and too costly and had never had them installed. To make matters worse, the management also established a policy to keep non-paying customers from slipping into the theater during a performance --- they quietly bolted nine pair of iron panels over the rear doors and installed padlocked, accordion-style gates at the top of the interior second and third floor stairway landings. And just as tragic was the idea they came up with to keep the audience from being distracted during a show. They ordered all of the exit lights to be turned off! One exit sign that was left on led only to ladies restroom and another to a locked door for a private stairway. And as mentioned already, the doors of the outside exits, which were supposed to make it possible for the theater to empty in five minutes, opened to the inside, not to the outside.

The investigation led to a cover-up by officials from the city and the fire department, who denied all knowledge of fire code violations. They blamed the inspectors, who had overlooked the problems in exchange for free theater passes. A grand jury indicted a number of individuals, including the theater owners, fire officials and even the mayor. No one was ever charged with a criminal act though. Families of the dead filed nearly 275 civil lawsuits against the theater but no money was ever collected. The Iroquois Theater Company filed for bankruptcy soon after the disaster. The Iroquois Theater Fire ranks as the nation’s fourth deadliest blaze and the deadliest single building fire in American history. Nevertheless, the building was repaired and re-opened briefly in 1904 as Hyde and Behmann’s Music Hall and then in 1905 as the Colonial Theater. In 1924, the building was razed to make room for a new theater, the Oriental, but the façade of the Iroquois was used in its construction. The Oriental operated at what is now 24 West Randolph Street until the middle part of 1981, when it fell into disrepair and was closed down. It opened again as the home to a wholesale electronics dealer for a time and then went dark again. The restored theater is now part of the Civic Tower Building and is next door to the restored Delaware Building. It reopened as the Ford Center for the Performing Arts in 1998.

But this has not stopped the tales of the old Iroquois Theater from being told, especially in light of more recent, and more ghostly events. According to recent accounts from people who live and work in this area, "Death Alley" is not as empty as it appears to be. The narrow passageway, which runs behind the Oriental Theater, is rarely used today, except for the occasional delivery truck or a lone pedestrian who is in a hurry to get somewhere else. It is largely deserted, but why? The stories say that those a few who do pass through the alley often find themselves very uncomfortable and unsettled here. They say that faint cries are sometimes heard in the shadows and that some have reported being touched by unseen hands and by eerie cold spots that seem to come from nowhere and vanish just as quickly.

Chicago Fire Dept.- Iroquois Theatre Fire

https://youtu.be/spzAGnNwaUg

The 1903 Iroquois Theater Fire - Chicago (HQ)

https://youtu.be/WARJ1YuJLTU

Iroquois Theatre Fire Documentary H 264 for Apple TV

https://youtu.be/LKOKWcnU8nA

The Iroquois Theater Disaster Killed Hundreds and Changed Fire Safety Forever

The deadly conflagration ushered in a series of reforms that are still visible today