Posted: 24th January 2015 by

The Hatching Cat in

Horse Tales

Tags:

Brooklyn Fire Department,

Engine Company 205,

FDNY,

FDNY history,

fire horses,

New York History,

Pacific Hose Company

4

The Last Run

“Once more, the picturesque is to yield to the utilitarian. That thrilling sight – three plunging fire horses drawing engine or hook and ladder – one of the few thrilling sights to be seen in our prosaic streets, is soon to become a thing of the past. Within the next five or six years, there will not be a fire horse in Greater New York. The gasoline motor will do the work of these old favorites.”– New York Times, February 19, 1911

The Fire Department of New York began motorizing the department and replacing its fire horses in 1910 with the purchase of a motor-propelled hose wagon and water tower.

The Fire Department of New York began motorizing the department and replacing its fire horses in 1910 with the purchase of a motor-propelled hose wagon and water tower.

Up until 1865, fire engines and hose carts were pulled through the streets of New York by the volunteer firemen. Horse-power replaced manpower with the organization of the paid departments in 1869, and for the next 50 years, horses did the hauling and the heavy work.

By 1911, Chief Croker had already been responding to the big fires in his own motorized vehicle. But 33-year-old Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo, pictured here, was the first to propose motor-driven fire apparatus for the FDNY. On March 17, 1911, Waldo told The New York Times: “The horse is sure gone as far as the fire business is concerned. It’ll do for pleasure, but it’s out of the business.”

By 1911, Chief Croker had already been responding to the big fires in his own motorized vehicle. But 33-year-old Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo, pictured here, was the first to propose motor-driven fire apparatus for the FDNY. On March 17, 1911, Waldo told The New York Times: “The horse is sure gone as far as the fire business is concerned. It’ll do for pleasure, but it’s out of the business.”

In 1910, under the watch of Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo and Chief Edward F. Croker, the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) tested its first motor-driven apparatus. The vehicle, stationed at Engine Company No. 72 on East 12th Street, was a high-pressure hose wagon that carried 40 lengths of 50-foot hose and could go an amazing 30 miles an hour on good roads or 25 in heavy snow (the horse teams could go only about 15 to 18 miles an hour, and this speed decreased with every mile traveled).

That year, the city also introduced its second motorized firefighting apparatus – a motor-propelled water tower. This vehicle, the first of its kind in the world, could go 20 miles an hour and plow through snow and mud with ease to assure speedy arrival at a fire (the heavy horse-driven tower was always the last to arrive on scene because it was a challenge for even the strongest horses.)

Not only could the gas-propelled water tower go faster than a horse-driven tower, it could also be backed into narrow streets or alleys where fire horses could never get.

The first motorized apparatus of the FDNY was a 1909 Knox high-pressure hose wagon, shown here in front of Engine Company No. 72 at 22 East 12th Street (today the Cinema Village theater). This hose wagon was one of the first three firefighting vehicles to simultaneously arrive on the scene of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire on March 25, 1911. Photo, Museum of the City of New York Collections.

The first motorized apparatus of the FDNY was a 1909 Knox high-pressure hose wagon, shown here in front of Engine Company No. 72 at 22 East 12th Street (today the Cinema Village theater). This hose wagon was one of the first three firefighting vehicles to simultaneously arrive on the scene of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire on March 25, 1911. Photo, Museum of the City of New York Collections.

On March 16, 1911 – nine days before the Triangle fire – the city tested the very first “automobile fire engine.” Bright red, 20 feet long, with two seats and a 110-horse power motor, the $20,000 Nott fire engine could pump 700 gallons of water a minute at a pressure of 125 pounds. It featured 4 red, solid rubber wheels with chains to keep it from skidding as it “whizzed” 30 to 40 miles an hour through city streets.

In 1911, there were about 1,550 fire horses in service with the FDNY. The day after the new engine was tested,

The New York Times declared that the motorized apparatus was “the death knell of the fire department horse.”

The first motor-propelled water tower of the FDNY was tested and put into immediate service at 87 Lafayette Street, which housed both Engine No. 31 and No. 1 Tower Company. This firehouse was built with horses in mind, and featured three doors that opened automatically as the fire bell rang so the 17 horses could charge out. The interior was completely converted for use with motorized equipment in 1912. Photo, Museum of the City of New York Collections

The first motor-propelled water tower of the FDNY was tested and put into immediate service at 87 Lafayette Street, which housed both Engine No. 31 and No. 1 Tower Company. This firehouse was built with horses in mind, and featured three doors that opened automatically as the fire bell rang so the 17 horses could charge out. The interior was completely converted for use with motorized equipment in 1912. Photo, Museum of the City of New York Collections

Two years later, on March 12, 1913,

Commissioner Joseph H. Johnson Jr. announced that Fire Department of New York City would not purchase any more horses. Those horses still in service were to be retired as fast as possible and replaced with motorized vehicles. Since the average department life of a horse was five years, and there were still about 1,400 fire horses, Johnson estimated the department would be completely motorized within four or five years.

The transition went slower than expected. It was not until 1922 that the last horse-drawn engine responded to a call.

Before I talk about the last call, you may want to

check out this fascinating short video produced by the Aurora Regional Fire Museum that shows the fire horse in action.

The Last Call: Engine 205 of Brooklyn Heights

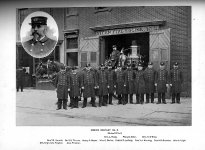

In the 1890s, Engine Company No. 5 had four horses: Tom, Dick, Jerry, and Speed. The horses were under the care of driver Michael O’Neill, pictured here with the reigns. As the only engine company house in Brooklyn Heights and the closest to City Hall, Company No. 205 was always on stage, so to speak. Visitors often stopped by to see the horses or watch the men practice to see how quickly they could respond to a call.

In the 1890s, Engine Company No. 5 had four horses: Tom, Dick, Jerry, and Speed. The horses were under the care of driver Michael O’Neill, pictured here with the reigns. As the only engine company house in Brooklyn Heights and the closest to City Hall, Company No. 205 was always on stage, so to speak. Visitors often stopped by to see the horses or watch the men practice to see how quickly they could respond to a call.

Engine Company No. 205 of Brooklyn Heights was the last fire company in the FDNY to become motorized. Part of the delay was due to World War I, but another was due to nostalgia: Engine 205 was Brooklyn’s oldest, most famous, and most influential fire company. It was organized September 19, 1846, by young, upstanding men from wealthy families of downtown Brooklyn.

Commanded by Foreman Henry B. Williams, its first members included William Wright, Edward Merritt, F. H. Macy, John W. Mason, George C. Baker, H. H. Cox, Clinton Odell, Henry Haviland and George E. Brown.

When Pacific Hose Company No. 14 switched from their hand engine, shown here, to a new steam engine, one of the men wrote an ode to the old engine: “Farewell, old gal, a long farewell; Your days of usefulness are o’er; Who can your future life foretell; When you have left your native shore? Perhaps amid the marshy fields of old New Jersey you may roam; Or some Long Island town will claim your ponderous beauties as her own…”

When Pacific Hose Company No. 14 switched from their hand engine, shown here, to a new steam engine, one of the men wrote an ode to the old engine: “Farewell, old gal, a long farewell; Your days of usefulness are o’er; Who can your future life foretell; When you have left your native shore? Perhaps amid the marshy fields of old New Jersey you may roam; Or some Long Island town will claim your ponderous beauties as her own…”

Back then it was a volunteer company called Pacific Hose No. 14 – the “Dude” Company of the Heights. Pacific Hose was first stationed on

Love Lane near Henry Street, but sometime around 1855 it moved into more spacious quarters at 160 Pierrepont Street (then near the corner of Fulton Street).

Assistant Fire Chief Smokey Joe Martin, who once commanded the aforementioned dual-company on Lafayette Street, and who was the inspiration for the naming of Smokey Bear, sounded the last alarm for the last horse-driven engine in the history of the FDNY.

Assistant Fire Chief Smokey Joe Martin, who once commanded the aforementioned dual-company on Lafayette Street, and who was the inspiration for the naming of Smokey Bear, sounded the last alarm for the last horse-driven engine in the history of the FDNY.

The company became Engine No. 5 when the Brooklyn Fire Department formed in 1869. Then after the Brooklyn Fire Department merged with the FDNY in 1898, the company was renamed Engine Company No. 105 (in 1913 it became No. 205).

On the morning of December 20, 1922, Fire Commissioner Thomas J. Drennan, Brooklyn Borough President Edward Riegelmann, firefighters, Jiggs the firedog, and other city dignitaries gathered in back of Borough Hall to pay their final tribute to the fire horse.

At 10:15, Assistant Fire Chief Joseph B. Martin (Smokey Joe Martin) tapped out the final call at the fire alarm box at Joralemon and Court Street: 5, 93, 205. Translation: An engine is wanted, Station #93, let Company 205 answer.

When the alarm sounded, Balgriffen took his place in the middle spot of the hitch for the engine, with Danny Beg and Penrose on each side. George W. Murray drove the engine this day, although driver Louis Rauchut was also in attendance.

George W. Murray drives Balgriffen, Danny Beg, and Penrose on the final call for the last-horse-drawn engine in FDNY history. On the ash pan behind, Captain Leon Howard was keeping his hand on the whistle rope so that it screamed one long blast; Engineer Tom McEwen pushed coal into the firebox with both feet and one hand (he used his other hand to hold on tight).

George W. Murray drives Balgriffen, Danny Beg, and Penrose on the final call for the last-horse-drawn engine in FDNY history. On the ash pan behind, Captain Leon Howard was keeping his hand on the whistle rope so that it screamed one long blast; Engineer Tom McEwen pushed coal into the firebox with both feet and one hand (he used his other hand to hold on tight).

Waterboy and Bucknell hooked up to the hose wagon, with veteran John J. Foster (“Old Hickory”) at the reins and driver William T. Daly on the sidelines.

The horses dashed down Fulton Street and along Court Street to Joralemon Street, and then to the rear of the Borough Hall. There, Jiggs, the senior coach dog, ran circles around the engine, obviously anxious and confused why no one was hooking up to the hydrant or dragging the nozzle.

Deputy Fire Commissioner Thompson, Jiggs, and the last fire horses of the FDNY. Brooklyn Times Union, December 21, 1922.

Jiggs, the long-time coach dog and mascot of Engine Company No. 205, howled in sorrow as his horse friends were bid their final farewell.

Jiggs, the long-time coach dog and mascot of Engine Company No. 205, howled in sorrow as his horse friends were bid their final farewell.

The muster ceremony ended as Riegelmann placed wreaths on each horse and the press photos were taken. Then the five last fire horses of the FDNY were swapped for a new motorized engine and hose wagon. The old horse-drawn equipment would be sent to a small town or village. Balgriffen, Danny Beg, Penrose, Waterboy, and Bucknell were reportedly retired to either light duty on Blackwell’s Island or to upstate farms operated by the ASPCA.

In my next post, I’ll tell you about

a special farm in upstate New York where retired fire horses grazed alongside New York City’s alcoholics and drug addicts.

For now, I’ll leave you with a

really amazing video of Fire Chief John Kenlon as he drives on the sidewalk to avoid traffic jams and barely misses hitting numerous pedestrians and trolley cars while responding to a fire call in his motorized vehicle in 1926. (Don’t miss the old traffic control platform — what they used before traffic lights — at about 2:13.)

Enjoy!

Within the next 5 or 6 years, there will not be any fire horses in New York. The gasoline motor will do all the work.”-- NY Times, Feb. 1911

hatchingcatnyc.com